Churchill through the lens of Professor David Reynolds.

Don't miss the insightful conversation where David shares behind-the-scenes details and inspirations for his newest masterpiece in the video below the review.

Signed editions available at our bookshops and online.

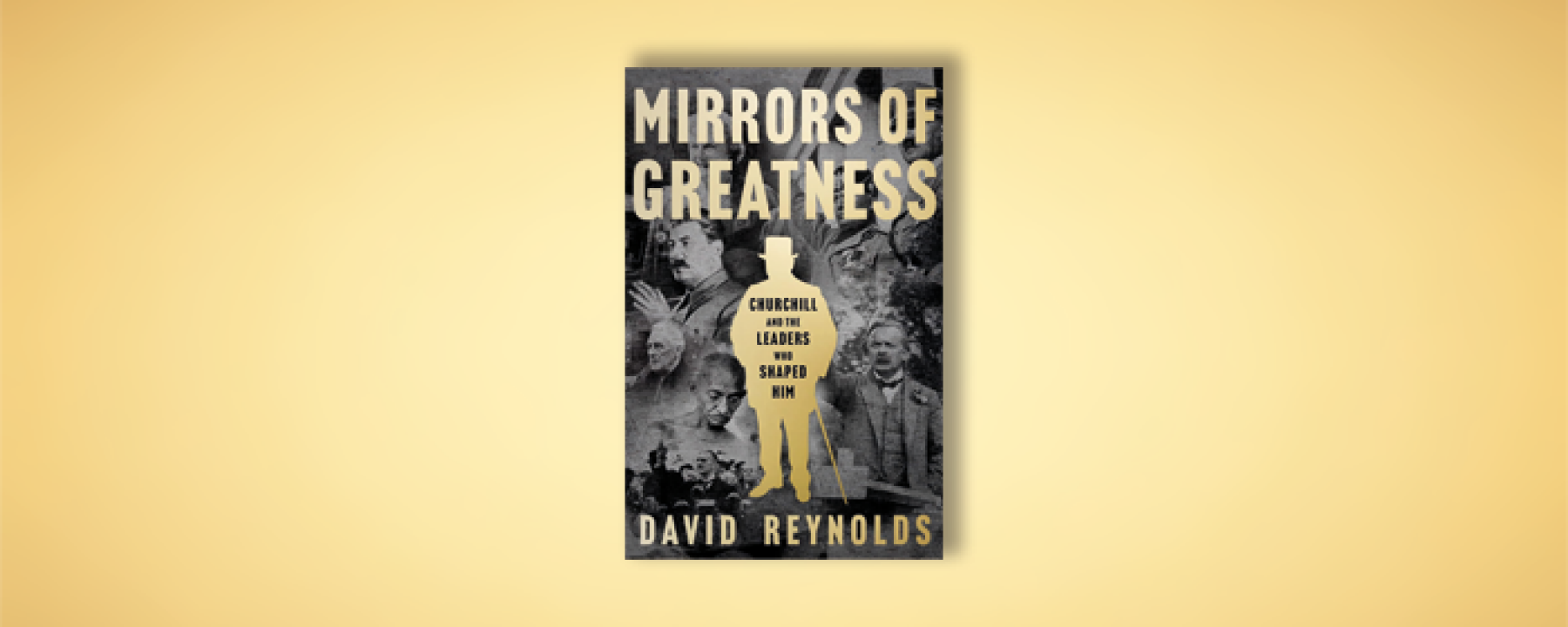

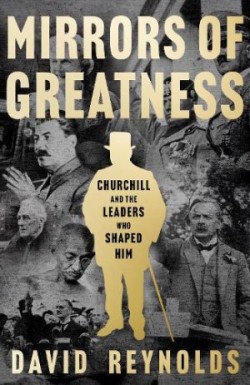

Mirrors of Greatness

David Reynolds

Mirrors of Greatness: Churchill and the Leaders Who Shaped Him, by David Reynolds. William Collins, 2023.

There are probably two types of readers of this review. There are the Churchill or World War II fans. And there are the rest of us, who appreciate Churchill’s importance but don’t necessarily understand the ceaseless torrent of books and films dedicated to celebrating (or attacking) his achievements. David Reynolds has written a book that will delight and inform both types.

Cambridge historian Reynolds, a hugely experienced scholar of British foreign policy, has written a Churchill book with a difference. Mirrors of Greatness explores how Churchill related to a selection of the great men (and one woman) of lifetime, and shows how Churchill’s own conscious effort to achieve ‘greatness’ was shaped by the way he perceived these personalities. The result is a fascinating and multi-layered portrait that can tell us much about Churchill and the ways in which he thought about a range of his most crucial contemporaries, from Hitler to his wife, Clementine. This is not simply a new twist on the familiar Churchill story, but a vital way of making sense of Churchill. This is because, as Churchill obsessively pursued immortality as a statesman, these ‘mirrors of greatness’ as described by Reynolds formed the context in which Churchill would define ‘greatness’. And his interactions with them – hero-worship, enmity, respect, derision – helped determine Churchill’s own highly erratic but ultimately triumphant career.

Reynolds dedicates a chapter to each of the individuals who influenced Churchill, starting with his father and ending with Clementine. In between are chapters on fellow British Prime Ministers David Lloyd George, Neville Chamberlain, and Clement Attlee, and a cast of twentieth-century political giants: Hitler, Mussolini, Roosevelt, Stalin, de Gaulle, and Gandhi. These chapters can easily be read in isolation, but are neatly woven together chronologically to enable something like a biographical picture of Churchill to emerge.

What makes this book so enjoyable is that Churchill was not a neutral, academic observer of greatness and great leaders. As Reynolds points out: Churchill ‘saw what he wanted to see’. This means that his worldview and personality quirks sometimes led him to draw conclusions that readers today would find baffling. Churchill devoted little time to considering Hitler as a leader, considering the militarised German nation to be far more menacing. As a staunch anti-socialist, Churchill remained well-disposed towards the Fascist Mussolini even when ranged him as the wartime Prime Minister of Britain. His Mussolini was a tragically flawed hero who had been seduced into the Nazi embrace by what Churchill referred to as ‘Mad dreams of imperial glory’ for twentieth-century Italy.

Mirrors of Greatness

Reynolds, DavidChurchill, as contemporary critics are now vocalising more loudly than ever, was himself an ardent imperialist. His faith in the British Empire and its virtues for the wider world was rooted in Victorian racial paternalism. It caused him to despise Mohandas Gandhi. Churchill’s ideal colonial subject was masculine and martial: a proud, loyal ‘native’ supporting the Empire. Thus, the image of the dhoti-clad Gandhi invoking civil disobedience over issues such as taxes on salt presented Churchill with something unfathomable. He hated him. As Reynolds puts it:

What really got under Winston’s skin was that Gandhi was not playing the familiar game … Worse still, his creed of political non-violence could not be overcome by force, and that challenged everything Winston had understood about power.

A more ambiguous aspect of Churchill’s vision of leadership emerges from his relationship with Neville Chamberlain. One might think that Churchill’s approach and attitude would contrast sharply with that of the appeaser Prime Minister, but as Reynolds sees it, it wasn’t so simple. In particular, Churchill would take Chamberlain’s belief in the power of personal diplomacy by way of ‘summitry’ and embed them into his handling of Roosevelt and Stalin during World War II. What failed utterly for Chamberlain at Berchtesgaden became a pillar of the Churchill myth, familiar to us all as the cigar-totting British bulldog cementing the grand alliance over copious doses of vodka and champagne at Tehran and Moscow. Moreover, there was something reminiscent of Chamberlain’s calamitous misreading of Hitler’s personality in Churchill’s bizarre insistence that ‘Joe’ was a reasonable and honourable negotiator once he was freed from Kremlin supervision. Perhaps this kind of wishful thinking was not so very different from Chamberlain’s belief in ‘peace for our time’ after Munich.

Whether you are a Churchill fan or a critic, Mirrors of Greatness is a beautifully written and expertly realised kaleidoscope that offers new way to appreciate the man and his place in the pantheon of world leaders.

Interview